Dual abelian variety

In mathematics, a dual abelian variety can be defined from an abelian variety A, defined over a field K.

Contents |

Definition

To an abelian variety A over a field k, one associates a dual abelian variety Av (over the same field), which is the solution to the following moduli problem. A family of degree 0 line bundles parametrized by a k-variety T is defined to be a line bundle L on A×T such that

- for all

, the restriction of L to A×{t} is a degree 0 line bundle,

, the restriction of L to A×{t} is a degree 0 line bundle, - the restriction of L to {0}×T is a trivial line bundle (here 0 is the identity of A).

Then there is a variety Av and a family of degree 0 line bundles P, the Poincaré bundle, parametrized by Av such that a family L on T is associated a unique morphism f: T → Av so that L is isomorphic to the pullback of P along the morphism 1A×f: A×T → A×Av. Applying this to the case when T is a point, we see that the points of Av correspond to line bundles of degree 0 on A, so there is a natural group operation on Av given by tensor product of line bundles, which makes it into an abelian variety.

In the language of representable functor one can state the above result as follows. The contravariant functor, which associates to each k-variety T the set of families of degree 0 line bundles on T and to each k-morphism f: T → T' the mapping induced by the pullback with f, is representable. The universal element representing this functor is the pair (Av, P).

This association is a duality in the sense that there is a natural isomorphism between the double dual Avv and A (defined via the Poincaré bundle) and that it is contravariant functorial, i.e. it associates to all morphisms f: A → B dual morphisms fv: Bv → Av in a compatible way. The n-torsion of an abelian variety and the n-torsion of its dual are dual to each other when n is coprime to the characteristic of the base. In general - for all n - the n-torsion group schemes of dual abelian varieties are Cartier duals of each other. This generalizes the Weil pairing for elliptic curves.

History

The theory was first put into a good form when K was the field of complex numbers. In that case there is a general form of duality between the Albanese variety of a complete variety V, and its Picard variety; this was realised, for definitions in terms of complex tori, as soon as André Weil had given a general definition of Albanese variety. For an abelian variety A, the Albanese variety is A itself, so the dual should be Pic0(A), the connected component of what in contemporary terminology is the Picard scheme.

For the case of the Jacobian variety J of a compact Riemann surface C, the choice of a principal polarization of J gives rise to an identification of J with its own Picard variety. This in a sense is just a consequence of Abel's theorem. For general abelian varieties, still over the complex numbers, A is in the same isogeny class as its dual. An explicit isogeny can be constructed by use of an invertible sheaf L on A (i.e. in this case a holomorphic line bundle), when the subgroup

- K(L)

of translations on L that take L into an isomorphic copy is itself finite. In that case, the quotient

- A/K(L)

is isomorphic to the dual abelian variety Â.

This construction of  extends to any field K of characteristic zero.[1] In terms of this definition, the Poincaré bundle, a universal line bundle can be defined on

- A × Â.

The construction when K has characteristic p uses scheme theory. The definition of K(L) has to be in terms of a group scheme that is a scheme-theoretic stabilizer, and the quotient taken is now a quotient by a subgroup scheme.[2]

Dual isogeny (elliptic curve case)

Given an isogeny

of elliptic curves of degree  , the dual isogeny is an isogeny

, the dual isogeny is an isogeny

of the same degree such that

Here ![[n]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/de504dafb2a07922de5e25813d0aaafd.png) denotes the multiplication-by-

denotes the multiplication-by- isogeny

isogeny  which has degree

which has degree

Construction of the dual isogeny

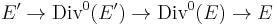

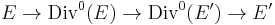

Often only the existence of a dual isogeny is needed, but it can be explicitly given as the composition

where  is the group of divisors of degree 0. To do this, we need maps

is the group of divisors of degree 0. To do this, we need maps  given by

given by  where

where  is the neutral point of

is the neutral point of  and

and  given by

given by

To see that ![f \circ \hat{f} = [n]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/2551d35f907fc8696d998b2fe7984e53.png) , note that the original isogeny

, note that the original isogeny  can be written as a composite

can be written as a composite

and that since  is finite of degree

is finite of degree  ,

,  is multiplication by

is multiplication by  on

on

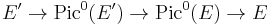

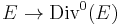

Alternatively, we can use the smaller Picard group  , a quotient of

, a quotient of  The map

The map  descends to an isomorphism,

descends to an isomorphism,  The dual isogeny is

The dual isogeny is

Note that the relation ![f \circ \hat{f} = [n]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/2551d35f907fc8696d998b2fe7984e53.png) also implies the conjugate relation

also implies the conjugate relation ![\hat{f} \circ f = [n].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/c39a72888135907d2619c34d1a701c9c.png) Indeed, let

Indeed, let  Then

Then ![\phi \circ \hat{f} = \hat{f} \circ [n] = [n] \circ \hat{f}.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/52a8f1b62fd3e66d105788f6046f2503.png) But

But  is surjective, so we must have

is surjective, so we must have ![\phi = [n].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/e956d4f3807fe630953315741c82028c.png)

Notes

References

- Mumford, David (1985). Abelian Varieties (2nd edition ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195605280.

This article incorporates material from Dual isogeny on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.

![f \circ \hat{f} = [n].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/0041b6d809e10375191498ab967a7c8c.png)